If you’ve spent any time exploring awareness practices, there’s a good chance you’ve asked yourself whether self-inquiry, presence, and mindfulness are really just different labels for the same thing. I hear this question constantly, and it makes sense. All three deal with awareness, all three involve stepping back from the noise of thought, and at a glance, they look almost identical.

But after years of sitting with each one, making mistakes with each one, and watching other people struggle with the same confusion, I can tell you they’re not interchangeable. And the cost of mixing them up isn’t just theoretical. When people treat self-inquiry like another flavor of mindfulness, they almost always hit a wall. It starts to feel like the practice isn’t doing anything, and that frustration pushes a lot of people to give up on it entirely, which is a real loss.

If you want genuine clarity on how these methods differ, when each one is most useful, and why the distinction actually matters in practice, keep reading. This guide sorts through the confusion using practical, real-life language and concrete examples.

Why These Practices Get Confused

I get why people end up stuck on this. Mindfulness, presence, and self-inquiry all involve awareness, and all of them help you get some distance from the constant pull of thoughts. The “awareness” piece seems obvious enough: you’re just noticing what’s going on, right?

What isn’t so obvious, though, is where your attention is actually being directed in each practice. It’s a subtle difference, easy to miss, but it completely changes the texture of what you experience and the results you walk away with. All three of these methods help you be less tangled up in thinking, sure. But the underlying goal and the way you work with attention are genuinely different.

If you’ve ever sat down to practice self-inquiry only to realize it felt pretty much like regular mindfulness, this is almost certainly the reason.

What Is Mindfulness?

Mindfulness has gotten a lot of attention in recent years, and for good reason. It’s accessible, it works, and you don’t need any particular background or belief system to start.

Here’s how it tends to look in practice, whether I’m doing it myself or walking someone else through it:

Paying attention to whatever is happening right now, often with a focus on the breath, body sensations, or ambient sounds.

Noticing thoughts and emotions as they surface, but letting them move through without grabbing onto them or pushing them away.

Nonjudgmental awareness: you’re not categorizing things as good or bad, you’re simply seeing them.

A real-life example might help. Say I get a stressful email at work, something that gets under my skin immediately. If I use mindfulness, I’d bring my attention to my breathing or to the feeling of my feet on the floor, and I’d just notice what’s happening in my body. The tightness in my chest, the racing quality of my thoughts. I’m watching all of it, but I’m not trying to fix anything or push the stress away. The whole point is to be with the experience, whatever shape it takes, without getting pulled into a reaction. I’m the observer here, not the fixer.

That approach is genuinely helpful for anxiety, emotional overreactions, or simply for waking up out of autopilot mode. And the key thing to notice about mindfulness is this: I’m watching what’s happening, but I never really question who is watching. I’m not even particularly interested in myself as the observer. I’m just tracking the flow of experience, moment by moment.

Wherever You Go, There You Are – Jon Kabat-Zinn

If you want a grounded introduction to mindfulness without spiritual complexity, this is one of the clearest starting points. Kabat-Zinn presents mindfulness as direct, present-moment awareness — simple, practical, and applicable to daily stress. It’s a strong foundation for learning how to observe thoughts and sensations without immediately reacting to them.

For more on this, the guide on Presence vs Mindfulness breaks it down really clearly.

What Is Presence?

Presence is a term you’ll come across a lot in the work of teachers like Eckhart Tolle. It’s less about following specific steps and more about landing in the raw, direct feeling of being here, that simple living sense that “I am.”

In practice, tuning into presence might look like:

Feeling the direct sense of aliveness in your body, the warmth or subtle energy in your hands, chest, or face.

Getting fully absorbed in listening to sounds or seeing colors around you, not thinking about them, but actually meeting them.

Letting go of the past and the future long enough to arrive right here, in this moment.

If you’re caught in a mental loop about an old argument or replaying a conversation from last week, presence is what happens when you let all of that fall away for even a second. You’re just here. No story, no strategy, just the simple fact of being alive in this moment.

Presence doesn’t ask for a mental label, and it doesn’t require any structured technique. That’s part of what distinguishes it from mindfulness, which generally involves specific objects of focus and a more intentional framework. Presence is direct contact with simple being, wordless and immediate.

There’s certainly overlap with mindfulness, but in practice, mindfulness tends to be more structured, like deliberately bringing attention to the breath or body, while presence is more of a felt quality you tune into.

As a side note, presence can break you out of mental loops fast, particularly if you’re someone who tends to ruminate or get caught in overthinking spirals. I often recommend it to people who feel disconnected from their life or their body, or who just need something to pull them back into the ground of the present moment.

That said, both mindfulness and presence are still oriented toward the content of awareness, what’s showing up in experience. Neither one asks who is aware.

The Power of Now – Eckhart Tolle

This book popularized the modern understanding of presence as direct awareness of the present moment. Tolle emphasizes stepping out of mental time and reconnecting with the simple fact of being here. If you want to explore presence as a lived, felt experience rather than a structured technique, this is a strong place to start.

What Is Self-Inquiry (Ramana Maharshi)?

Self-inquiry, as Ramana Maharshi actually taught it, is a different kind of practice altogether. It isn’t about passively watching experience, and it isn’t just mindfulness with a philosophical twist.

The core move is this: you’re turning attention toward the sense of “I,” the one who’s experiencing everything.

Here’s what that looks like. A thought or emotion arises, say I’m irritated by a rude message from someone. Instead of getting swept into the irritation or simply observing it from a distance, I ask: “To whom does this arise?” The answer: “To me.” But instead of stopping there and following that thought, I turn my attention toward the sense of “me” or “I” that the thought appears to. Not the word, not the label, but the actual felt sense of being myself, the root feeling of “I am.”

Then I rest attention there, on that sense of “I,” and let everything else quiet down naturally. Nothing is being forced or suppressed.

This isn’t a mechanical exercise, and it’s definitely not about repeating “Who am I?” like a mantra, hoping something clicks. It’s also not a philosophical puzzle you’re trying to solve with logic. Self-inquiry is a felt, direct movement of attention. You’re looking for where the sense of “I” actually comes from. Ramana was very clear about that distinction.

If you want more detail on the method itself, the write-up on Ramana Maharshi Self-Inquiry Practice walks through it step by step.

So, to return to our earlier scenario: if I’m stressed about a work problem, self-inquiry means I pause, notice that anxiety is present, and then turn my attention toward the “I” who is experiencing that stress. It’s a bit like stepping backward, behind the story, into the raw sense of yourself before any label or narrative gets attached.

Over time, this loosens the grip of identification with thought. You stop automatically believing you are the story your mind is telling. That shift is quiet but significant.

Be As You Are – David Godman

This is one of the clearest introductions to Ramana Maharshi’s teaching in his own words. Compiled and edited by David Godman, the book centers on self-inquiry as Ramana actually explained it — turning attention toward the sense of “I” rather than analyzing thoughts. It’s an excellent starting point if you want direct guidance without philosophical abstraction.

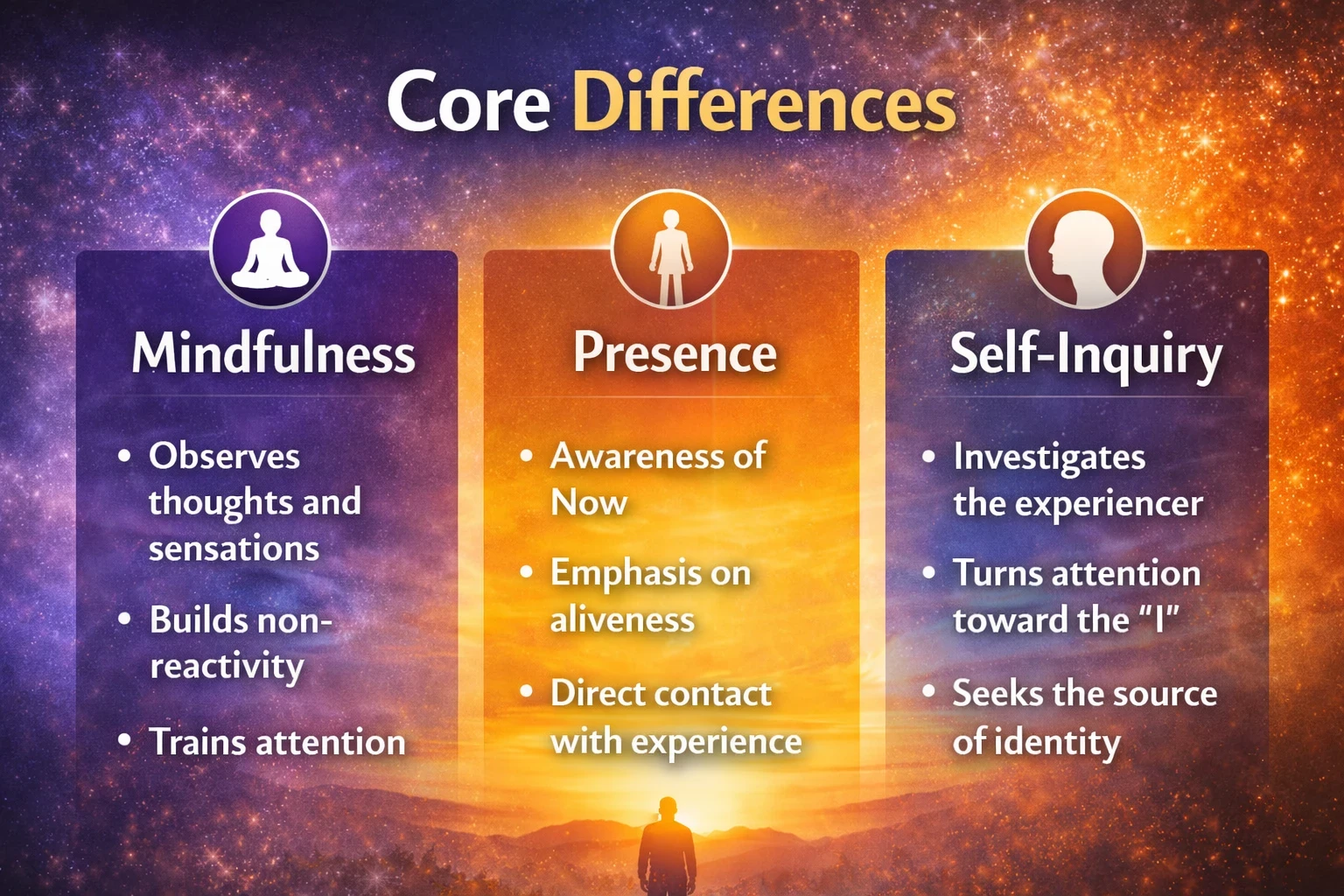

Core Differences

Mindfulness: Watching thoughts, emotions, or body sensations as they arise. It builds calm, trains attention, and helps you break the habit of reacting immediately. Your attention stays with the flow of experience.

Presence: Centered on the alive feeling of being here now. Less structured than mindfulness, more about tuning into the quality of existence in this moment. It still works with experience, but it sharpens your sensitivity to what it actually feels like to be present.

Self-Inquiry: Looking into the one who’s watching. You’re not centered on the breath or on sensations; you’re tracing every perception back to the sense of “I.” Attention turns onto the experiencer, not just the experience.

Bouncing between these practices without understanding the different direction of each one leads to frustration, and that’s especially true with self-inquiry. The method only opens up when you understand what you’re really doing with your attention.

Awareness of Experience vs Investigation of the Experiencer

One of the most helpful ways I’ve found to picture this difference: mindfulness and presence both help you watch the “movie” of life, the thoughts, feelings, hurts, victories, stories, and sensations. With mindfulness, you’re picking up on the details of the scene. With presence, you’re feeling the living energy of the scene itself.

Self-inquiry is like turning away from the screen entirely and looking at the projector, or the light that makes the whole movie possible.

In real, practical terms, that means you shift your attention away from the stressor, the hectic thoughts, even the pleasant feelings, and you ask who it’s all happening to. Then you rest in the witnessing “I.”

This isn’t just a concept. You can try it right now.

Sitting at your desk, you notice anxiety about an upcoming deadline.

Mindfulness: You notice the physical sensation, name the anxiety, and bring attention to the breath.

Presence: You drop out of the anxious thought loop and tune into what it feels like to simply be sitting here, alive, in this room.

Self-inquiry: You ask who feels this anxiety, follow the thread back to “me,” and then rest in that bare sense of “I” before any story about the deadline comes in.

When to Use Each Practice

Mindfulness: Extremely practical when you’re in the grip of immediate emotional reactivity, anger, anxiety, frustration, the whole range. It’s also useful for everyday stress, autopilot living, and simply building patience. If a harsh email or a rushed morning has your nervous system firing, mindfulness is excellent for creating a little space without trying to battle your thoughts into submission.

Presence: Particularly helpful if you catch yourself lost in memories, regrets, or daydreams about the future. Use presence to land back in your body, get out of your head, and reconnect with what’s actually happening around you. Try it while walking, doing chores, or spending time with friends, moments where you realize you’ve been mentally somewhere else.

Self-inquiry: Works best when your mind has some degree of calm and isn’t spinning out in a strong emotional reaction. It’s the practice to reach for when you want to question the root sense of identity, the feeling of “I” itself, usually when you’re settled enough to be genuinely curious about the deeper source of the mind.

Presence and mindfulness are both reliable for steadying the mind and handling everyday stress. Self-inquiry is more direct, and it goes deeper, but it asks for a certain readiness. When you’re in the middle of a big emotional wave, that’s not usually the moment for self-inquiry. I generally recommend starting with mindfulness or presence to settle things down, then moving into self-inquiry once there’s some inner quiet to work with. This combination tends to work well for most people.

If you’ve experienced self-inquiry feeling flat or ineffective, especially with a restless mind, the article on Why Self-Inquiry Fails goes into the common reasons.

Common Mistakes

Doing self-inquiry as just another flavor of mindfulness, watching thoughts come and go but never actually turning attention back toward the “I.”

Alternating between practices at random, never staying with one long enough to feel its particular effect or gain any real traction.

Expecting some kind of dramatic, mind-blowing realization to hit you in the first few sessions, rather than patiently working with your attention over time.

Trying to answer “Who am I?” with ideas, with philosophy, or by repeating the words and hoping an answer drops in, instead of looking for the nonverbal, felt sense of “I.”

One trap I see often: people approach self-inquiry as a question that needs an answer, as if the right sentence or concept will eventually appear and solve everything. That’s not how it works. The practice is about staying curious with the “I” itself, not about confirming what you already think you know about it.

Final Clarification

Each of these practices works. They’re just moving your attention in different directions, and they meet different needs at different times. Ramana Maharshi called self‑inquiry the most direct route to the root of self‑identity, but he did not dismiss other mind‑calming practices; he treated them as supportive yet secondary to direct self‑inquiry.

Terms like “mindfulness” and “presence” are contemporary labels; here they are being mapped onto Ramana’s broader framework of calming the mind and turning attention inward, rather than quoted as words he himself used.

Those practices play a real role in grounding and steadying the mind, and that foundation matters.

There’s no need to pit these methods against each other or declare one the winner. The real power comes from understanding what you’re actually doing in each one. Mindfulness builds the skills to observe and pause. Presence grounds you in the immediacy of being alive. Self-inquiry cuts to the core when you’re ready to look at the most basic fact of being “me.”

FAQ: Self-Inquiry, Presence, and Mindfulness

Is self-inquiry the same as mindfulness? Not really. Mindfulness is about watching thoughts or sensations as they arise, while self-inquiry turns attention toward the sense of “I,” the experiencer behind those thoughts. The direction of attention is fundamentally different.

Is presence just another word for mindfulness? No. While they share some common ground, presence is about the direct, felt sense of being alive right now, not just observing what happens. It’s less structured and more immediate.

Can mindfulness lead to self-inquiry? Yes, it can. Mindfulness calms the mind and sharpens attention, which naturally creates the conditions where you’re ready to question the sense of “I” more directly.

Which practice is deeper? Self-inquiry goes to the root of who you are. Mindfulness and presence are genuinely valuable, but self-inquiry is specifically focused on the source of identity itself.

Did Ramana teach mindfulness? No. Ramana’s central teaching was self-inquiry, turning attention toward the self. He acknowledged the value of practices that calm the mind, but his primary instruction was always to investigate the “I.”

Now Put It Into Practice

If this distinction helped you see what you’ve actually been doing in practice, don’t leave it at theory. Try it.

The next time stress or irritation shows up, notice which direction your attention moves. Are you watching the experience? Are you grounding into presence? Or are you tracing the sense of “I” back to its source?

If you want a step-by-step explanation of Ramana Maharshi’s actual method, read Ramana Maharshi Self-Inquiry Practice.

And if self-inquiry has felt confusing or flat in the past, Why Self-Inquiry Fails goes deeper into the most common mistakes.

If you want to see the distinction between self-inquiry and presence explained step by step, watch the full video where I break it down in practical terms.

Clarity changes everything. Once you know where attention is moving, the practice becomes simple.

Chris is the voice behind Daily Self Wisdom—a site dedicated to practical spirituality and inner clarity. Drawing from teachings like Eckhart Tolle, Ramana Maharshi, and timeless mindfulness traditions, he shares tools to help others live more consciously, one moment at a time.Learn more about Chris →

Leave a Reply